Murphy & AllisonAllison Manufacturing Company

|

| “The works occupies an

enclosure of about five acres of ground, situated between the West Chester

and Junction railroads, and extending from Walnut to Spruce streets, in

West Philadelphia. Nearly all of this extensive area is covered with

buildings, generally of brick and stone, one and two stories in height.

The greater portion of the building fronting on Walnut street is devoted

to painting cars, the shop for the purpose being two hundred and

fifty-nine feet long and eighty-one feet wide. Many of the workmen

employed in this department are not merely good mechanical painters, but

artists, whose productions, if on canvas, would be entitled to a place in

a gallery of Fine Arts. On the second floor of this building are the

varnishing rooms, and also a room eighty-one by forty feet used as an

erecting shop for city passenger cars [streetcars].” “Adjoining the building just mentioned is a fire-proof [!] structure, the lower floor of which is appropriated to offices and counting-rooms, including a fire-proof safe, which is a small room in itself, being sixteen feet long by nine feet wide, and on the upper floor are the upholstering department, pattern rooms, and rooms for the storage of valuable material. All the doors and girders in this building are of iron, and the structure is believed to be indestructible by fire. The inner office is arranged with a view of facilitating the clerk who acts as time-keeper. All the workmen make their entrance and exit through one gateway, and each man, as he enters, receives a small metallic number which he returns when he leaves the yard. By means of a spring the clerk in charge of the gateway can close it without leaving the office, and all workmen who come late are known and registered.” “A large space of ground between the painting and erecting shop is appropriated to the transfer table, over which is an arched bridge connecting the second stories of the two buildings. Beyond is the erecting shop, two hundred and forty feet in length, eighty feet wide, and where may be seen Cars [sic] in their various stages of progress, among them some of the first class, with raised roofs and facilities for ventilation, such as approach as near perfection as the art has as yet attained. Adjoining the erecting shops on the south, are the wood working shops, one for hard, another for soft lumber; and also the repair shop, the machine shop and the engine room. The greater portion of the floor above these shops is appropriated to pattern and cabinet-making, for which it is equipped with all of the most approved tools and best machines. West of these buildings, and detached, are the blacksmith shops. In the bending room is a boiler in which wood is steamed preparatory to being bent to the various curvelinear and irregular forms desired. All of the rooms are heated in winter by means of steam pipes, of which there are about eight miles [emphasis of the reporter] distributed in coils through the different apartments. The condensed water of all these pipes is brought back and collected, to be used again to supply the boilers.” “In this extensive establishment about three hundred men are employed, though doubtless nearly double that number, if needed, could operate without inconvenience, and it has a capacity for turning out every week three large passenger cars, ten street cars, and thirty freight cars, without interfering with the General Jobbing and Repairing [caps the reporter’s]” |

According to one authority {245}, Allison quit building passenger cars altogether about 1868.

In that year, John George Brill—a German immigrant who had worked for Allison for more than 25 years and had risen to the position of foreman of the streetcar shop—resigned his position with Allison and started his own streetcar-building business which would ultimately become the J.G. Brill Company.

Following the shop fire of 1863, Allison had built new shops in west Philadelphia. But in 1872 these shops too went up in flames. {42} Nevertheless, in 1873 Allison was judged capable of producing 6,000 freight cars annually.

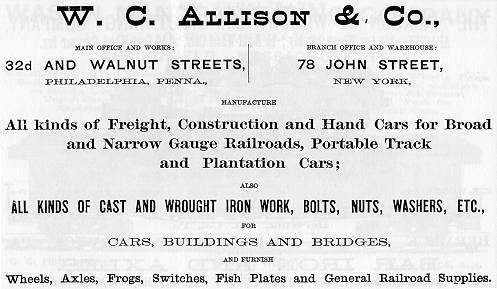

Somewhere along the line between 1866 and 1883, the Allison firm experienced another change in ownership or organization, as its advertisement in the 1879 Car Builders Dictionary represents it as W.C. Allison & Co.

|

|

(1879 edition, Car-Builders Dictionary) |

In 1881, Allison built a special car for the Virginia & Truckee to transport the locomotives of its narrow gauge Carson & Colorado subsidiary over broad gauge rails for maintenance. This thirty foot, 25 ton capacity flat car with narrow gauge rails affixed, became V&T engine transfer car No. 1. It was probably used to haul mining machinery as well. In 1938, it was sold to Paramount Pictures, and was probably used to move its narrow gauge prop engines from location to location.

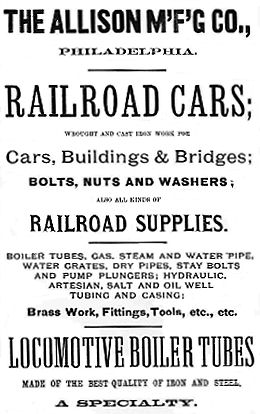

In 1883, the firm was incorporated as the Allison Manufacturing Company.

|

(1887 edition, Poor’s Directory of Railway Officials) |

No doubt through their earlier connection with Edward Knight, their Philadelphia connection, Allison was engaged to build the four sleeping cars for T.T. Woodruff & Company in 1888 that became a key element in the latter’s contract with the Pennsylvania Railroad to run a sleeper service much like that later offered by Pullman.

Allison quit the railway car field before the turn of the century.