New York Elevated Railroad - Page 3

|

|

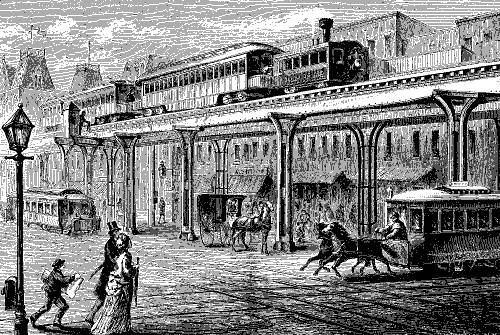

Charles Harvey making a test run 7 December 1867. |

The line opened for business 1 July 1868, and—the State Commissioners who authorized the “experiment” having declared it a success—the Governor authorized its completion to Spuyten Duyvil (once a creek flowing into the Hudson River that separated the northern tip of Manhattan Island from the Bronx “mainland” and is now a ship channel connecting the Hudson and the Harlem rivers).

But the line had ongoing problems. The mechanics of grasping the cable proved less-than-perfect. Maintaining the mile-long cable was a problem. Having it “return” under the street was a problem that was soon fixed by having it return at track level, but it still had to be directed off the track and into the building where the stationary engine sat. Legal problems were constant, largely at the instigation of those who wanted the franchise for themselves.

And on top of these various costs came, in September 1869, “Black Friday,” as Gould and Fisk failed in their attempt to corner the gold market. The ensuing depression made it hard to finance anything, but somehow by April 1870, the line was extended as far as 32nd Street via 9th Avenue, for a total length of almost four miles, with two intermediate stations and a total of four stationary engines driving the cables.

|

|

Cable car #1 of the West Side and Yonkers Patent Railway Company. The racks for the cable can be seen beneath the track. Shown 1869 at the original up-town 29th Street Station. |

Nevertheless, the line finally shut down altogether, and its assets were sold 15

November 1870 for all of $960 (about $15,000 in today’s money). The

purchasers of this bargain outfit were the bondholders, who subsequently

reorganized the line as the Westside Patented Elevated Railway Company.

In February 1871, the new company was given permission to use steam power, and by April—after strengthening the superstructure—operation began with tiny steam locomotives (one of the first rated 5 tons). Looking back several years later, a contemporary magazine article says,

|

“The Greenwich Elevated Railway [sic], which at first was a total failure as long as several stationary engines were used, moving the cars by means of a wire rope, has become a decided success since the employment of small locomotives, each pulling two or three quite long cars.” {1} |

|

But in the summer of 1871, three mortgages were defaulted, and trustees were appointed by the bondholders to reorganize the railroad properties. In 1872, the property was bought at auction by the newly organized New York Elevated Railroad Company.

THE SOO CANAL

In 1852, while in Northern Michigan recovering from a bout of typhoid, Charles Harvey heard that Congress had passed an act granting 750,000 acres of federal land to any company that could build a canal around Saint Marys Falls, connecting Lake Superior and Lake Huron. Harvey persuaded his employer, the Fairbanks Scale Company, to build the canal. Despite the fact that he was a salesman and accountant, he became the primary contractor and engineer. Learning on the job, he built the Sault Sainte Marie (Soo) Ship Canal, which opened in 1855.

THE WORK OF RUFUS GILBERT

Rufus Henry Gilbert (1832 -1885) was the son of an associate judge in Steuben County, NY. He had limited schooling, but while working as a drugstore clerk studied classical literature, mechanics, and mathematics at night. He later prepared himself to enter the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City.

Gilbert spent time in London and Paris following the death of his wife, ostensibly to study their hospital systems, but came home convinced that cities of the day needed more healthful conditions, and that rapid transit was a way of providing them.

When he arrived back at New York City, the Civil War was just beginning, and he immediately enlisted. A physician of unusual ability, he became Medical Director of Fortress Monroe, and later Director and Superintendent of the United States Army Hospitals. At the end of the war he became assistant to Josiah Stearns, Superintendent of the Central Railroad of New Jersey.

Gilbert investigated many different ideas for elevated railroads, but was never able to come up with anything practical. In 1872 he came up with the idea of using "atmospheric tubes" to propel cars (somewhat like the vacuum lines used to move documents from one place to another in the outdoor teller windows of some banks). He received a charter 12 June 1872 for the Gilbert Elevated Company.

He resigned from the Jersey Central, but due to the Financial Panic of 1873, was unable to secure financing. It would be almost four years before construction would begin.

For More Information —

Hornung, Clarence P. Wheels Across America. South Brunswick and New York, NY: A.S. Barnes and Company, 1959, pp. 198-219.

History of all kinds of wheeled transportation, from bicycles on up, has a number of pages on streetcars and elevated railroads. Very few photos, but extensive illustration using contemporary woodcuts and engravings.

Ratigan, William. Young Mister Big. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1955.

Story of the builder of the Soo Canal which united Lake Superior and Lake Huron - Charles T. Harvey. A traveling salesman who went to Lake Superior for a vacation and stayed to build the Soo canal.

Reeves, William Fullerton. The First Elevated Railroads In Manhattan And The Bronx Of The City Of New York: The Story of Their Development and Progress. New York, NY: The New-York Historical Society, 1936.

An excellent history, with many photos of the lines and structures. Few photos of equipment. 137 pp.

Sansone, Gene. Evolution of New York City Subways; An Illustrated History of New York City’s Transit Cars. Brooklyn, NY: New York Transit Museum Press, 1997.

Comprehensive history of MTA New York City railcars. Extensive array of photographs and line drawings. Mr. Sansone is Assistant Chief Mechanical Officer of Car Equipment Engineering and Technical Support for MTA New York City Transit, and the introduction to his work says, "Produced by the Division of Car Equipment, MTA New York City Transit." 390 pp.

Online:

Katz, Wallace B. “The New York Rapid Transit Decision of 1900: Economy, Society, Politics.” Historic American Engineering Record. Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service, National Park Service, Department of the Interior. Washington, DC. (From which much of the above article has been abstracted.)

“The Progress of Elevated Railways”. Scientific American Magazine, Vol. XLI.-No. 17, October 25, 1879.