Davenport & Bridges - Page 2

In 1842, the Davenport & Bridges works were moved to the

south side of Main Street, where they occupied the entire block between

Portland Street and Osborn. They would remain the largest single plant in

Cambridgeport until after 1850. {425}

A description of the works was published in

the American Railroad Journal in 1848. This description was picked

up by the Cambridge Chronicle and is reflected in the following

from Leaders of Cambridge Industry:

{439}

| “To the three-story brick building fronting on

Main Street, two large wings were added in 1848, extending on Osborn

Street, known as the east and west wings. [Main Street running

roughly east and west.] The west wing, facing on Osborn Street, was

about three hundred and fifty feet long by forty feet wide.

[Slightly more than the length of a modern football field from goal

post to goal post.] The east wing extended parallel to the other

wing, with an open area between. This building was two hundred and

forty feet by forty-three feet, both wings were brick, two stories

high. One wing was used as a foundry and blacksmith shop, the latter

containing sixteen forges, while the other was used as a machine

shop. There were eight smaller buildings, most of them about one

hundred by thirty feet, some of them being two stories high. Over

one hundred men were employed.” |

Surprisingly, this works of the largest of

the earlier car builders never had a direct connection to any railroad!

Charles Davenport was one of the incorporators of the Grand Junction

Railroad, which was chartered in 1847and hoped to make a connection to his

car works, but by the time the railroad was completed in 1855, he had

retired and his works was shut down. But that’s getting ahead of our

story.

{439}

In 1842, Davenport & Bridges had orders in hand

for 800 cars.

{245}

The American Railroad Journal

{444} described cars built that year for the Auburn & Rochester Railroad

—

|

“The cars are each 28

feet long and 8 feet wide. The seats are well stuffed and admirably

arranged—with arms for each chair, and changeable backs that will allow

the passenger to change ‘front to rear’ by a

manœuvre [sic] unknown in military tactics. The size of the cars forms a

pleasant room, handsomely painted, with floor matting, with windows

secured from jarring, and with curtains to shield from the blazing sun.

We should have said rooms; for in four out of six cars, (the other two

being designed only for male passengers,) [sic] there is a ladies’

apartment, with luxurious sofas for seats, and in recesses may be found

a washstand and other conveniences.

... These cars are so hung on springs, and are of such large size, that

they are freed from most of the jar, and especially from the swinging

motion so disagreeable to most railroads.” |

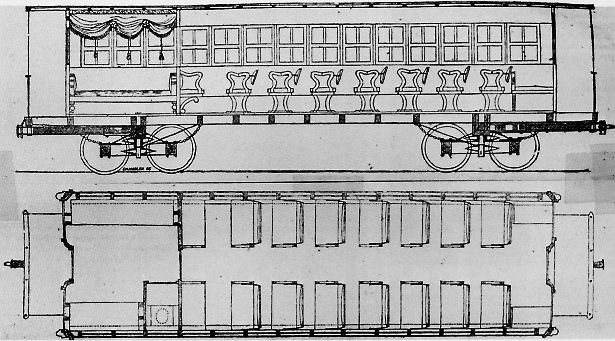

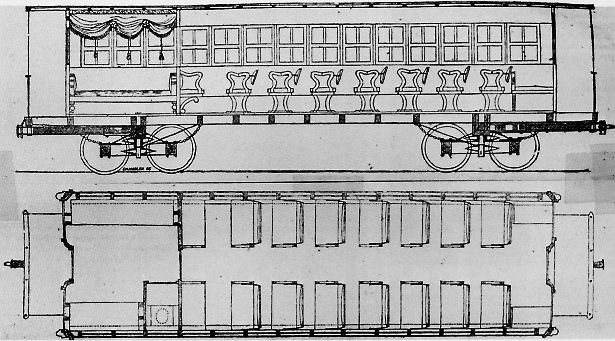

The drawings below were published several years later, but

seem to agree closely with the description above.

|

|

Davenport & Bridges built coaches like this probably from 1845 to

1860. The large “restroom” at the left end of the car, with its

longitudinal benches, was for the ladies. (Above, American

Railroad Journal, 7 August 1845. Below, American Railroad

Journal, 8 August 1846.) |

|

In 1844, Charles Davenport received Patent No. 3,697, dated

10 August 1844, for a metal truck with cross-bracing. Davenport says in his

application, “I do not claim making the truck frame of a rail road [sic] car

or carriage with side truss frames united with diagonal braces as this has

been known before, nor do I claim making these frames of iron or other metal.”

But then he continues to describe the way his truck is constructed.

Others had competing designs, including

Eaton & Gilbert and Fowler M. Ray,

who would later found the

New England Car Spring Company, promoting “springs” of India

Rubber.

Davenport also received other patents we haven’t identified

yet, and reportedly invented the reversible car seat, which eliminated the

need to turn cars at the end of each trip. (Note the seats in the

illustrations above.)

|