Jewett Car CompanyAkron Car Company

The story begins in Akron, Ohio, late in 1892. John F. Seiberling, who controlled the Akron Street Railway, decided to build his own car bodies. (Electrical equipment, being in its infancy, was probably too sophisticated to attempt.) He hired John C. Boyd (probably of the Canton Car Company) to manage the operation, established in a former car barn. The car barn quickly proved too small, and Boyd sought a better location. {408} The little town of Jewett, Ohio, about 50 miles from Akron proved to be the best prospect. Just as industries do today, he offered employment for 100 men if the town would donate land and raise capital. Three acres near the Pennsylvania railroad were donated, and a $10,000 bonus raised. And by May 1893 work had begun on a 70' by 250' building which would be completed by late summer. {408} But the national economy would have much to say about the future of the Jewett enterprise. Just about the time the new building was started, the New York Stock Exchange began a severe contraction; foreign trade had already been declining, wheat and iron prices had turned down, and business activity had been slowing. On May 6th, the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad and the National Cordage Company failed. In June, Western and Southern banks withdrew more than $20 million from New York banks. By the time the dominoes stopped falling three to four years later, 15,000 commercial firms, 600 banks and 74 railroads, including the mighty Union Pacific, would fail. But to return to Jewett ... John Seiberling was forced to attend to his other, failing financial interests, and he turned the Jewett operation over to John Boyd, who in turn hired Neil Paulson as general manager. Paulson had been with the Pullmans Palace Car Company in Chicago, and as in modern executive moves, brought people with him who knew the business. {408} But the deepening depression had its effect, and in October 1894, Jewett voluntarily went into receivership with total assets of $26,000 [something over $0.5 million in today’s buying power] and outstanding debt of a little over $8,000. But the lengthening depression brought business to a standstill and for the next three years Jewett was closed as much as it was open. {416} Late in 1897, Jewett was acquired by a group of investors in Wheeling, West Virginia, who incorporated it under the laws of that state as the Jewett Car Company and Planing Mill. As economic conditions were indeed looking up, a 50' by 160' addition was built to the plant, and by the following year business was picking up. In February 1898, Jewett had 50 to 60 men producing three street cars a week, with orders from St. Louis, Missouri; East St. Louis, Illinois; and Wheeling, Parkersburg and Moundsville, West Virginia. {416} But business picked up so fast that the capacity of the Jewett plant was insufficient, and its owners began looking for another location. This was a modern business: looking for further donations of land and capital. And they soon found it in a larger city. Newark, Ohio, just west of Columbus, would be Jewett’s third home. {416}

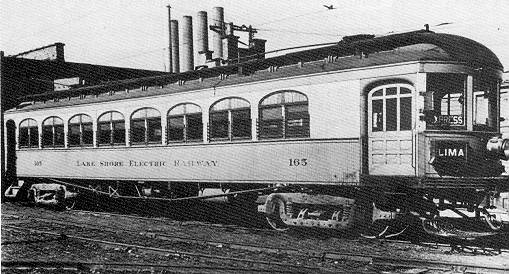

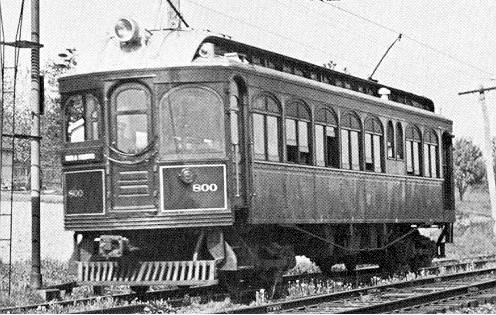

Newark offered everything Jewett needed: an experienced labor pool; donated land, located on not one but two railroads, with already existing buildings and room to expand; and a significant cash bonus. And not to be overlooked, Jewett’s West Virginia owners already had connections there. {417} By January 1900, some Jewett men were busy building additions to the plant, while others were moving machines and materials from the old location, and still others were beginning to assemble new cars. By mid-year, a 50' by 300' erecting shop had been added, together with other smaller shops, additional experienced workmen had been hired, and Jewett was in full production. {417} By the end of the year, Jewett had produced some 118 cars, including an order for 30 from Chicago’s South Side Elevated Railroad. {418} In 1901, Jewett really hit its stride. As best can be determined, it produced some 163 cars, including 50 for the Brooklyn Union Elevated Railroad and 25 for the Cleveland Electric Railways. {418} By 1902, the company had become a leader in the field of electric cars, obtaining orders for elevated cars for Brooklyn, New York City and Chicago. It also built cars for Ohio’s Lake Shore Electric, Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley Transit Company, and the Chicago street lines. In mid-April 1905, Albert H. Sisson, general manager of the company, abruptly resigned. He had come with the company from Jewett, Ohio. Corporate secretary W.C. Gardner said relations between the company and Mr. Sisson were “friendly.” Questioned about his plans for the future, Mr. Sisson said he had none, but that he intended to take a “good rest” before again engaging in business. {409} (Shades of the modern day, when executives so often give their reasons for leaving as “to spend more time with my family!”) Less than two weeks later, while Jewett President William S. Wright was preparing to leave West Virginia to fill in for the departing Sisson, newspapers were announcing an attempt to form a combination of 15-20 of the leading streetcar manufacturing firms. One of those named was Jewett. Wright was asked to affirm or deny the announcement and refused to do either. The Newark Advocate speculated that if the company were not to be included, Wright would have said so, ergo, it must be included! {410} But after a great deal of planning, politicking and maneuvering, accompanied by a huge amount of publicity, the Street Car Builders Consolidation appears to have simply evaporated! During the time the prospective consolidation was being talked about, Jewett was building a special car for the University of Illinois. A professor in its Electrical Engineering Department had been impressed by the electric railway exhibits at the St. Louis World’s Fair and wanted a car he could use to teach student engineers about electric railroading. Besides being equipped with all kinds of measurement devices, the control systems that would ordinarily go underneath the car were incorporated inside the car body so they could be studied in operation. You can find a great deal more about this car, including pictures, at H. George Friedman’s fine website Twin Cities Traction; The Street Railways of Urbana and Champaign, Illinois. Brough and Grabner points out there is no evidence Jewett ever had a sales department. Its sales came through extensive advertising, participation in trade shows and referrals by satisfied customers. It attributes Jewett’s success largely to the innovations to car design made by Jewett’s president, William Wright. In a day when every railway’s Master Car Builder had his own ideas about car design, a surprising number accepted Jewett’s recommendations. By the time of Wright’s death in 1949 he would hold at least six patents related to railway cars, several not related, and may have applied for others. {419} The years between 1901 and 1915 were good ones for traction builders, and especially for Jewett, although there were the expected dips caused by the general business conditions of 1907 and 1910/12. Brough and Grabner points out that “although Jewett is best remembered for its big wooden interurbans, the vast majority of its production was in city cars, either surface, elevated, or subway.” {420}

But all good things come to an end, and the end of good times came in 1915 for Jewett. The U.S. economy had begun to decline in mid-1914 as war began in Europe (the 1st World War). The railroads were in trouble. Costs—especially labor—were rising, taxes had been increased, and government was holding down rates. Demand for cars dropped precipitously. Complicating the situation, Jewett was offered the opportunity to produce munitions to support U.S. allies in Europe, but the company had to refuse, because a principle stockholder—a strong German nationalist—threatened to withdraw his financial backing if it did so. In April of 1917, the United States entered the war, and in December the government took over the railroads. Early the next year it placed orders for more than 100,000 cars—freight cars—helping Jewett not one bit. In December of 1918, Jewett went into receivership. As an independent concern in a specialized field, it did not have the resources to sustain it in the wartime economy. The receiver attempted to sell the Jewett plant, and came close with the Elgin Motor Car Company, but in the end agreement was impossible. A year later it was purchased by William Hamilton of the Erie Car Works, and operated for a few years as a car repair facility. While Jewett is primarily remembered as an interurban car builder, it also built a great many streetcars. Jewett streetcars were still running in Chicago until 1950, and in San Francisco until after 1955. Cast of Characters —William Shrewsbury Wright (1865-1949) was born in Cincinnati, Ohio. He attended the common schools there, and then studied engineering at Ohio State University. Then he moved to Wheeling, West Virginia, where he was employed about 1892 as an engineer to manage the reconstruction of the worn-out Wheeling Railway Company. The railway was reconstructed and renamed the Wheeling Traction Company, and in 1894 Wright became its general manager. Shortly thereafter, he left, performed a similar operation on the Wheeling & Elm Grove Railway and became its general manager. This was the position he held when the Wheeling syndicate purchased Jewett in 1897. {421} Wright became Jewett president, a job he held until the company went out of business in 1919. But he stayed in West Virginia and continued to manage the Wheeling & Elm Grove until forced to move to Ohio by the resignation of Jewett’s general manager Albert Sisson in 1905. {421} In 1900, Wright and two associates bought the bankrupt Newark [Ohio] & Granville Street Railway Company, which they operated for a few years before selling out. This appears to have been during the time he was moving the Jewett company to Newark. {421} Wright was a practical engineer, with a number of patents to his credit. At least six of these pertained to electric railway cars. Brough and Grabner cites the following, and says, “he also applied for patents for rotary track sweepers and an electric signaling apparatus.” But it gives no indication why patents might not have been issued on these applications. {421}

For More Information —“North Jersey Rapid Transit, Jewett.” Traction PlanBook. Newton, NJ: Carstens Publishing, 1964, p. 40.

“Observation Interurban from Fort Dodge.” Model Railroader, November 1961.

Brough, Lawrence A. and James H. Graebner, From Small Town to Downtown A History of the Jewett Car Company, 1893-1919 (Railroads Past and Present). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2004.

Hanson, Helen, John David Harriman and Malcolm Elliott. History of Jewett. Freeport, OH: Freeport Press, 1953-54. |